Dear Harbour,

The HATS story would not be complete without a note on its sustainability achievements. The project was designed and constructed in accordance with eco-friendly objectives and principles, and these also guide its ongoing operation. As the largest ever sustainable infrastructure project in Hong Kong, HATS has created a template for future sewage collection, treatment, and disposal infrastructure development in our city.

Water Quality

HATS was initiated primarily to tackle harbour water pollution, and so water quality improvement in Victoria Harbour is our single most important sustainability objective.

In its 2016 Annual Report on Marine Water Quality, the Environmental Protection Department said this of Victoria Harbour: “Water quality has been improving significantly with the progressive implementation of the Harbour Area Treatment Scheme, particularly after the commissioning of HATS Stage 2A in December 2015.”

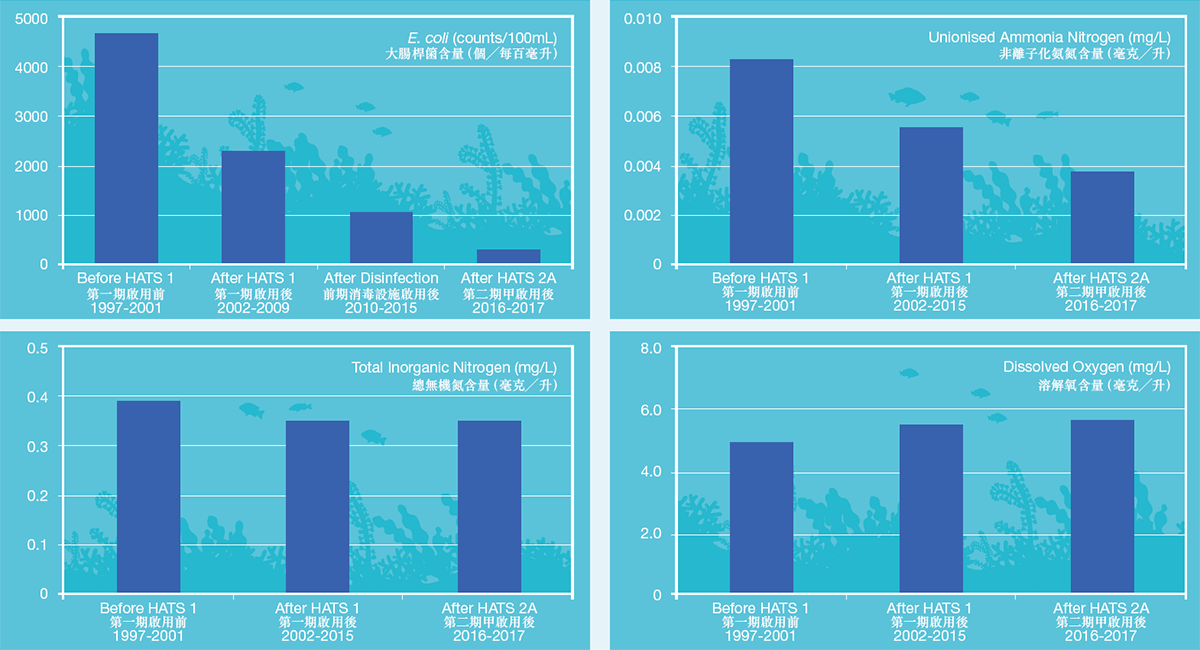

Water Quality Improvement Since Implementation of Harbour Area Treatment Scheme

The report goes on to say that the Water Quality Objectives (WQO) compliance rates for Dissolved Oxygen, Unionised Ammonia Nitrogen and Total Inorganic Nitrogen were 100%, 100% and 80% respectively in 2016, as compared with only 50%to 90% in the 2011–2015 period. The overall annual geometric mean E. coli level in the harbour was also down to around 300 counts per 100 millilitres, a tenfold reduction from the late 1990s.

Biodiversity is also on the increase, as exemplified by coral colonies and other aquatic life thriving again in the harbour. “Soft coral found living in Victoria Harbour points to cleaner water,” reported the South China Morning Post in August 2014, echoing similar articles in other media.

Another environmental milestone was achieved in 2011 with the resumption of the annual Cross Harbour Race in the eastern part of the harbour. The event had been suspended since 1978 due to harbour pollution. In 2017, the race finally returned to its original route in the central part of the harbour after 40 years — a testament to improving water quality. Secondary water contact activities and events such as dragon boat racing are now held in Victoria Harbour throughout the year.

The Cross Harbour Race finally returned to the central part of Victoria Harbour in 2017

Sing Tao Daily of 10 October 2004

Sustainable Project Design

The HATS project is sustainable at many levels. From the design and operation of the deep sewage tunnels and the Stonecutters Island Sewage Treatment Works (SCISTW), to the waste-to-energy disposal of the dewatered sludge from SCISTW and the greening and landscaping of the various enhanced Preliminary Treatment Works (PTWs), every facility and process aims to reduce energy consumption, minimise carbon emissions, and conserve natural resources.

The HATS economic model is self-sustaining and its relationship with its neighbourhood is harmonious.

Energy Efficiency and Conservation

The collection and transportation of sewage consume a lot of energy. HATS has adopted the “inverted siphon” principle in the design of its deep sewage tunnel system, achieving significant savings in energy. Furthermore, sewage levels in the drop shafts of upstream PTWs are monitored by sensors that provide real-time data to the pumping control system on SCISTW. This serves to optimise pumping energy without causing overflow upstream.

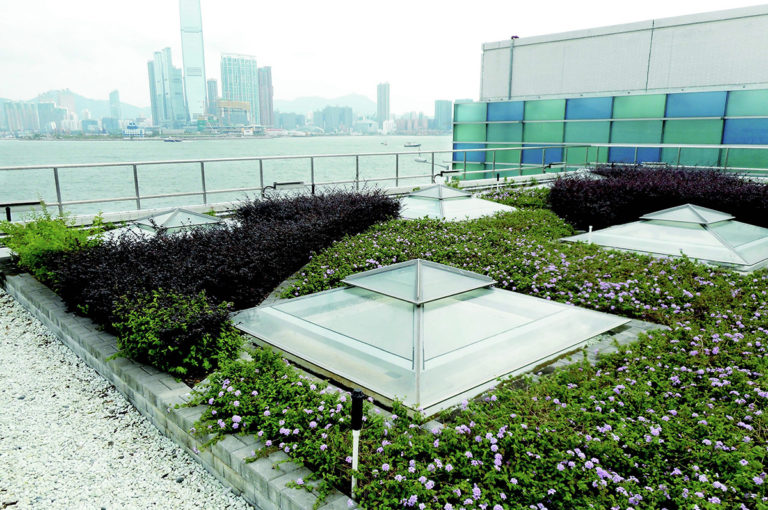

A key environmental feature of SCISTW is the Sludge Dewatering Facility which converts wet sludge into sludge cakes. These are transported by two sludge vessels to the T · PARK at Tuen Mun for incineration and electricity generation, a good example of the waste-to-energy principle in action. Other eco-friendly and energy-saving facilities adopted at SCISTW include insulated glass glazing, daylight sensors, energy-efficient variable refrigerant volume air-conditioning, skylights, green roofs, photovoltaic panels, solar water heaters, and energy-efficient lighting — many of which are adopted at PTWs, too.

The DSD is also adding new green features. As part of a pilot scheme, a hydro-turbine system has been introduced to utilise sewage flow hydraulic energy to move turbine impellers that in turn drive a generator to produce electricity for SCISTW. The system can generate up to 120,000 kWh of electricity per year, reducing energy cost and carbon emissions.

Hydro-turbine system at SCISTW

Greening, Landscaping and Neighbourhood

The SCISTW and PTWs are designed to be aesthetically pleasing, with lots of greening and landscaping. Additional greening features have also been introduced, such as bioswales and rain gardens that remove pollutants from stormwater runoff. Permeable pavements with grasscrete panels are used in place of hard concrete pavements to allow rainwater to drain more easily into the soil and thus to avoid flooding — an application of the “Sponge City” concept.

Greening and landscaping at North Point PTW

Permeable pavement with grasscrete panels at North Point PTW

We also take proactive measures to reduce noise and odour nuisance to residential developments near the SCISTW and PTWs. Furthermore, green roofs have been incorporated in the design of buildings and structures to improve aesthetics.

Green roof at Wan Chai East PTW

Curtain wall at Wan Chai East PTW

Green roof at SCISTW sludge dewatering facility

Green roof at SCISTW Main Pumping Station No. 2

We also meet community aspirations by opening up some areas originally designated to operation and maintenance for people’s enjoyment. A good example is a direct route through the Cyberport PTW, now opened to the public for easy access to the seaside promenade. Planned fencing works there have also been replaced by beautification and planting works to make the access route more pedestrian friendly.

Access road and pedestrian footpath at Cyberport PTW

Another example is the Sai Ying Pun Junction Shaft area, connected to the promenade, which will only be closed during a short period annually for inspection and maintenance.

Sai Ying Pun junction shaft and adjacent paved area

Economic Sustainability

The introduction of a sewage charge and trade effluent surcharge based on the “polluter pays” principle has not only secured funding to offset ongoing operations and maintenance cost, but also helped raise public awareness of the importance of sewage treatment. It provides an incentive, too, for the trade and industries to reduce pollution. Under the Chemical Oxygen Demand reassessment mechanism, trades and industries that have good practices or provide treatment to reduce polluting loads can apply for a reduction in trade effluent surcharge.

The DSD is constantly exploring cost-saving measures to ensure the economic sustainability of HATS and other treatment facilities in terms of energy consumption, chemical usage, and asset management. Maintaining your water quality, our dear Harbour, is our long-term commitment. The economic sustainability of HATS is in place to help us keep our promise to you for the future.

Bird eye view of Central PTW

Green roof at Central PTW

Close-up of a skylight at Central PTW

POSTSCRIPT

“I was involved in the maintenance and operation work of HATS in its early days, and began participating in its overall management in 2014. That was the time when the scheduled commissioning of Stage 2A was imminent, and there was enormous pressure on the team. Fortunately, all the difficulties were eventually resolved and the full commissioning went smoothly.”

“We tried to apply renewable energy as much as possible in HATS, such as installing rooftop photovoltaic panels at the preliminary treatment works. We also installed hydro-turbines to tap the energy from falling sewage in the double-tray sedimentation tanks to generate electricity for internal use. This boosts cost efficiency and provides a good case for public education.”

MAK Ka-wai

Deputy Director,

Drainage Services Department